MAKING SPACE

SPIRITUALITY AND MENTAL HEALTH

The Mary Hemingway Rees

Memorial Lecture

World Assembly for Mental Health

Vancouver, July 2001

Julie Leibrich

Contact:

Dr Julie Leibrich

PO Box 2015,

Raumati Beach,

New Zealand.

Phone: +64 4 902 2382

email: seacoast@paradise.net.nz

This paper has been published in Mental Health, Religion and Culture, Vol. 5, Number 2, 2002.

3: THE MEANING OF SPIRITUALITY

7: PERSONAL STORIES ARE PRECIOUS

9: RELATING SPIRITUALITY TO MENTAL HEALTH

12: HEALING IS CONNECTION, NOT CONTROL

13: THE POLITICS OF DIFFERENCE

14: THE UNEASY DANCE OF MADNESS AND MYSTICISM

1: AT LAST WE MEET

Photograph[1]. Kapiti Island, 2000.

We all

have a capacity to hurt and be hurt, to heal and be healed.

I imagined you many times as I

sat at my desk in Raumati, early in the morning, looking out to Kapiti Island,

thinking about this talk. I tried to see

your faces. Look in your eyes. I wanted to know who I’d be talking to. I wanted to know what spirituality meant to you.

Sometimes, I spirited you over.

My imaginary audience. I brought

you onto the beach where I live and together we looked at Kapiti for

inspiration. So if any of you got a

strange tingle of being somewhere else recently…

Sometimes, as I worked on the talk I felt I got to know you, even

though we hadn’t met. I thought about

how some of you would be coming from a long way away, like me. Some of you would be here alone, maybe not

knowing many people. Others would be

meeting up with old friends the moment you arrived.

I thought who are we,

these people going to Vancouver? Why are

we getting together? A group of

survivors, family and friends, psychiatrists, nurses, researchers. Every one of us here has the capacity to hurt

and be hurt, to heal and be healed.

Would we be able to acknowledge that? Would we be able to communicate

with each other meaningfully at this conference?

I so hoped we would share more than just information and knowledge.

I hoped we would take the risk of relating our experiences to each other

– our uncertainties and fears, our discoveries and dreams, our deepest insights

about mental health. Because then, we

would really connect with each other

– on an individual and international level.

That way, we would enter the realm of healing for ourselves, each other

and the mental health system itself.

2: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF SIGNS

Photograph. Rooftop at Assisi, 1987.

We look

for a sense of connection, with ourselves, others, and the universe.

I will take a risk right now and tell you that I felt I was called

to give this talk, and I don’t mean by Professor Roy phoning New Zealand from

Canada!

We

don’t use words like vocation much any more.

Smacks of missionary zeal. Not

cool. To say one is called to do

something seems grandiose, pretentious.

Ideas of reference, perhaps? Yet

many of us look for signs. Especially

when we are lost. Or we just notice

them, when we make the space to do so.

Seeing signs can give us a sense of personal

significance, personal meaning in

life. They spell out our sense of

connection with the universe.

There were so many

coincidences surrounding my invitation.

Things far beyond my control and far beyond my imagination. Jung and Koestler would have been in their

element[2]! From my point of view, it could not have been

clearer that I was being called to give this talk, than if a golden dove had

landed on the roof of my house with a signed invitation in its beak.

But I had been very ill and wasn’t sure if I

would be able to prepare a lecture, or even travel to Vancouver. Also, the set

topic was vast. Although, my friend Ian

said “Spirituality and mental health?

Well that’ll be a short talk! Stand up, say ‘Hope and Acceptance’ and sit down

again.”

I knew I was no expert and also could only talk

from my limited Western perspective. I

said to my friend Robert “I don’t know of any culture that doesn’t have the concept of spirituality”. He grinned.

“You should come on down to the

Otago Medical School!”

I really didn’t know if I could do this, but I felt I was supposed to. I said to myself

“I’ll find the words”. What I meant, of

course, was “They’ll find me.”

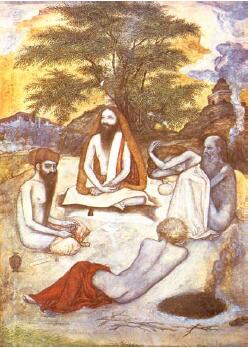

3: THE MEANING OF SPIRITUALITY

Painting. Gathering of Yogis.

Govardhan, 1620.

Spirituality

is a subjective experience, unique to each person.

The first question – and the one

I paused on for longest – was what do we mean by spirituality. I began to re-read familiar writers – C S

Lewis[3], Jung[4], John Donne[5], to remind myself what they said, but somehow I needed to move on from my loved

and familiar world of literature. I starting asking friends and acquaintances

“What does spirituality mean to you?”

Manda was succinct. “Knowing

you’re connected to everything.” Jim

was even briefer. “ Nothing.”

Dorothy, said “God!

I don’t know. It’s nothing to do

with churches. It’s more to do with

sunsets, the sea, things like that. The

open air and natural beauty. Water. And birds.

Definitely something to do with birds.”

Robert, said “I think it comes down to three

questions: Where do we come from? Where are we going? And why are we here?” Eric said “A

connectedness to some place. In my

younger days – a religion. Like knowing

a place. Knowing people.” Margaret

said “One of those glimmers in

time, when you have a feeling of how life really is, and the wholeness of it.” David told me that his son was a very spiritual person.

“He’s an atheist, mind you. But a very spiritual atheist.”

Then a young woman at the

hairdressers pulled me up short. She

turned the question on me. “Are you a spiritual person?” she

asked.

“Can you read my fortune?”

Everyone – I asked about thirty

people - said something different. I finally asked myself. What does it mean to me?

I had been avoiding the

question. It seemed too difficult, and

anyway, it’s always easier to get other

people to talk about the really hard topics in life, isn’t it?

4: SPIRITUALITY IS SPACE

Photograph. Ullapool Harbour, detail,

1993.

Spirituality

is a space where I find meaning and peace.

I

experience spirituality as space.

I call it the space within my heart. It is my most precious self. My spirit.

My soul. My essence. My being. It is the breath of life[6]. The innermost part of me.

It’s the place where I meet myself. It’s where I belong. It is where I find a sense of connection -

with my self, and with something beyond my self – a spirit greater than

myself. And sometime, very occasionally,

with another person, who is standing in their

space.

It

is the space I go into when I need to find meaning in my life, when I need to

come to terms with life or death, or when I need to accept that nothing stays

the same. It’s where I go when I need to

cope with the knowledge that I walk alone in this world, or experience the

comfort of infinite love.

It

is the space between reason and imagination.

Space where time is in different perspective, where things happen which

I could not have predicted. Space where

I feel loved, where I feel at peace, where I discover things.

It is a kind of coming home.

For me, the meaning of spirituality is meaning itself.

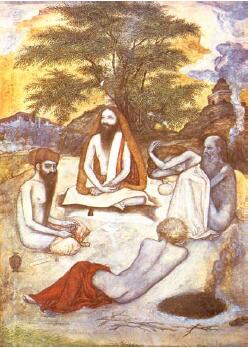

5: RELIGION IS INTERPRETATION

Illumination. The Evangelical Symbols. Book of Kells , 8th

Century.

Spirituality

is an experience whereas religion is an interpretation.

Spirituality is an experience, not a religion. Spirituality is beyond doctrine, beyond

cultural difference. It is something

deep within our core.

Religion is an interpretation

of the experience of spirituality. A

means of expressing it. A means of

honouring it. Religion shapes our

spiritual experiences because it is linked to culture, upbringing, a sense of

history, but it is not the experience itself.

Religion is also one of the ways we try to share our experiences

of spirituality, but this can be dangerous. It can actually create a barrier to sharing

spirituality.

Doctrine can be a divider.

An excuse for wars. Spirituality

is a connector. A reason for peace.

Religious

beliefs can be so easily misunderstood.

Even the simplest phrases we use to talk about our beliefs can be

alien. Let me

tell you a cautionary tale:

A few years ago. I was

writing a book on why people give up crime[7] and was interviewing a young woman about major changes in her

life. I was very aware that her

boyfriend, a heavy-duty gang member, had come out of jail the day before the

interview and was staying with her.

He wasn’t in the room but I felt ill at ease. I figured he was

having a rest – in fact, once or twice she talked about the man upstairs. How she only ever did what he wanted. I realised he was asleep and, to be honest, I

was glad not to meet him because he sounded a pretty bossy kind of

character. She seemed to worship him.

A week later, listening again to the tape, and really listening to the woman, rather

than worrying about myself, I realised she had been talking about God. She called him “The man upstairs.”

I also believe in the man upstairs, by the way. I believe that when I talk, he listens and

much more importantly, I believe that when I listen, he talks. But that

is a doctrine. My interpretation. The meaning I place on my spiritual

experiences. To say more now, might

create a barrier.

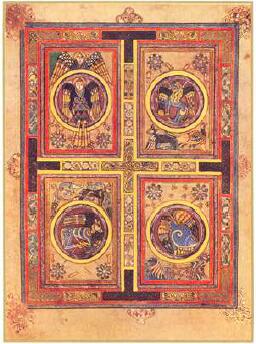

6: MENTAL HEALTH IS FREEDOM

Painting. I Dreamt I was in

Marseille. Matija Skurjeni, 1898.

Mental

health is the freedom of knowing and accepting one’s self.

Defining mental health is almost

as tricky as defining spirituality. It

is an another elusive concept and like spirituality, an utterly subjective

experience. For me, it means knowing who I am and

accepting that.

Mental health is the state of freedom which

comes from accepting one’s self and taking responsibility for one’s

actions. It is many other things as well

of course – acceptance of others as they are, acceptance of life as it is,

knowing when and how to change and when and how to let go.

My definition of mental health

has a lot in common with the way I define spirituality. Both concepts are concerned with the

experience of self. One reaching into dimensions of space to

discover self, the other realising the freedom that comes from accepting self.

That is why spiritual experiences and their interpretation can have such a

profound influence on mental health.

7: PERSONAL STORIES ARE PRECIOUS

Cover. A Gift

of Stories. Gathered by Leibrich, Otago University Press, 1999.

Relating

our experiences with others makes it possible for them to relate to us.

In my

last year as Mental Health Commissioner, I put together a book called A Gift of Stories[8]. This is a collection of

personal accounts of dealing with mental illness. Many of us in the book talked

about spirituality but I won’t try to sum

up what we said. Actually, I don’t want to.

Stories about people with mental illness have been summed up for too

long, by other people, in things called case histories, notes, files. Personal stories are not data to be

analysed. They are worth much more than

that.

When I first imagined A Gift

of Stories I saw something that would be precious. That is because personal

stories are precious. Stories

are the most wonderful way to talk about experience. A story is not just a plot or a theme. It is inextricably linked with character and

place and voice. A personal story often

reveals insight and has the power to

evoke insight within others.

I

wanted us to relate our experiences

because I wanted to make it possible for other people to make a connection with

their experiences through reading about ours. Through us.

To them.

Producing

the book – the telling and the gathering - was an act of love. A gift.

It taught me that illness can also be a gift.

8: ILLNESS CAN BE A GIFT

Photograph. Ullapool Harbour,

1987.

Illness

can make people discover a deeper, stronger sense of self.

In a Gift of Stories, I began by using the word recovery to describe how people dealt successfully with mental

illness. I wanted to challenge the

stereotype that people who experience mental illness never get better. But as I worked with the people in the book,

and we talked about this word, it began to seem too limited a concept.

Recovery is commonly used to

mean “Hey! Here I am! Completely better!” Yet this, as a goal, would deny the

experience of many people with ongoing experience of illness, for whom getting

well means learning how to manage the

illness – whether it comes in episodes or is ever-present.

Recovery can also imply that the

goal is merely to return to some prior state - to get back what you have lost,

or, worse, to cover yourself up again, or both.

To makes things the same as they were before. But this denies the power of illness, which often leads to new things.

Eventually I used the word discovery rather than recovery. Our stories were full of discovery - not just

about dealing with mental illness but

through dealing with it. I described dealing with mental illness as

“making our way along an ever-widening spiral of discovery in which we uncover

problems, discover the best ways to deal with them, recover ground that has

been lost, discover new things about ourselves, then uncover deeper problems,

discover the best ways… and so in an intricate process of growth.”[9]

I made a comment in the text

about being fearful of committing myself to the permanence of publication. I was right to be cautious.

A year later, I thought the word

transformation might have been better.

When someone experiences severe illness, it changes them. They are never the same again. People who have had to deal with mental

illness say that it gives them strength of character, a greater capacity for

compassion, a deeper, stronger sense of self.

Two years later, after my own

experiences of the last year, I wondered about the word transcendence. It means that

although we are ill, we are not imprisoned by that experience but go beyond

it. We transcend the illness and claim its

power. Illness teaches us about being well.

Vulnerability teaches us about being strong. Loss teaches us about finding.

Several people in our book called their

mental illness a gift. Sometimes I even

do so myself.

9: RELATING SPIRITUALITY TO MENTAL HEALTH

Photograph. Isle of Tiree, 1987.

Mental

illness can be a spiritual journey which leads to greater health.

Every time I have had an episode

of illness in my life, I have been on some kind of spiritual journey by the

time it is over. In the long term,

through these experiences, I see myself becoming more and more whole. In fact,

I see myself as a mentally healthy

person, who is sometimes ill.

When I experience severe

depression, I seem to lose my sense of self.

I feel like I am disintegrating.

Depression is a potential killer.

It puts everything into shadow.

Colours fade, voices and music become harsh. It whispers in my ear that life has no

value. Sometimes, it is as if I have

died, and the depression then becomes a state of mourning for the dead me.

When everything seems so

pointless and full of pain, I have to find some kind of comfort if I am to

survive. Although I need to accept the

illness, I also need hope.

Sometimes I have a kind of

miraculous experience, a kind of turning point which involves spiritual

insight. I know, deep within, that at

these times, I am healing. That is why I

have to reach the space within my heart[10] to get well. There are many ways into that space for me[11] - through reflecting with

gratitude on the things I have, through focusing on the smallest point of here

and now, through letting go of all the things I am trying to control. Almost always, though, the way in is through

silence and solitude.

Sometimes, it is too hard and I

am lost or locked out from myself. Then

maybe someone else can show me the way home through my connecting with them and

their spiritual self. Maybe they are able to say “I know what you’re going through. I’ve been there too”. Or maybe all they can say is “I don’t know what it’s like for you, but I

care and I’ll be there with you”.

Maybe they just take my hand and sit a while. I call such people soul mates.

Sometimes it is impossible to

reach out so I am not able to connect with another person. Sometimes I do not want to reach out, I need to reach in. Then, I am on a

different kind of journey, one that I have

to take alone. I can’t always tell the

difference until the journey is over.

Sometimes the best I can do is

wait and hold on to the belief that “this too will pass”.

I have had various treatments

for depression, including drugs, but I am ambivalent about medication. Once or

twice they have saved my life, but they also numb me and make it harder for me

to connect with my spirit. So in the

long run, they make it harder to heal. I

haven’t worked this out yet.

I also experience times of

intense joy and creativity. They are a kind of kaleidoscopic

switch-back where ideas travel at the speed of light. This is when I know that everything is

connected to everything else in the universe.

I look at a tree and see how

every leaf on that tree is connected with every other leaf on every other

tree. I have amazing dreams, sometimes

waking dreams, maybe mystical moments.

These are also often my source

of inspiration as a poet. Creativity is

the greatest spiritual experience I have.

Creativity is the act of giving breath to life, expressing the spiritual

world in the physical world.

Sometimes my highs are

frightening - when I get close to the edge of what I call a spin. If I cannot “manage them”, hold the clay in

shape, if you like, as it spins on the potter’s wheel, then I am in

trouble. I can become so exhausted by

the speed and intensity that I get physically ill.

So far in my life, I have never

allowed the joy to be viewed and treated as a mental illness and no external

force has insisted that it should be. I

know that I have been fortunate and often reflect that it might have been

otherwise.

Sometimes, I am not so sure that

I would have chosen this life, my life, if I’d been there on the edge

of time and had a say about it. I think

I’d have asked for something a bit easier from the man upstairs. “’Scuse me Guv. Do you think you could take out a bit of the

mood swing stuff and give me a bit more tranquillity.” But I think Guv would have turned round and

said, “Look Jules, this is all that’s on offer today. Take life while you can and accept it for

what it is and sometimes you’ll know the meaning of miracles.”

10: HEALTH MEANS BEING WHOLE

Photograph. Taj Mahal, detail, 1998.

When we are well, we see

ourselves as whole.

When we

are ill we can see ourselves as disintegrated.

We

are parts, and we are whole.

When

we are well, we experience ourselves as whole.

Health, literally means being

whole[12]. Healing means making whole. It is a

natural power - a power of nature. At my best, at my most spontaneous and

natural, there is no incongruity between being parts and whole. I am simply one.

When we are ill, it is less easy to see ourselves as whole. One of the most devastating experiences of

mental illness is that very sense of

not being whole – the disintegration of self.

We say we are “falling apart”, “coming apart at the seams”, “breaking

down”. Sometimes

I forget my wholeness – especially when I am ill – and I see my body as

separate from my mind. And sometimes I forget my body or my mind. Other times I see my spirit as so removed

from my mind and body that it doesn’t belong to them at all.

Any therapy which treats a person in a disintegrated way is not

just ineffective, it is actually harmful because it can reinforce the

disintegration of illness and erode a person’s innate power to heal

themselves.

11: WISDOM REQUIRES INSIGHT

Photograph. Sunset at Stigliano, 1998.

Spirituality and mental

health are understood through insight, not information.

In the Middle Ages there were

three kinds of proof: Reason, Authority,

and Experience[13]. By the end of the nineteenth century we had

narrowed it down to one: scientific evidence.

But whose evidence are we

talking about?

At present, the dominant model of health

care in the western world – the one

which gets the funding - is based on biological determinism which sees illness

primarily, if not totally, as having physical causes. This model, by definition, sees people in parts, rather than as whole. Even models which call themselves “holistic” or “integrated” often act as if people were in parts.

Clinical trials are one of modern medicine’s

greatest strengths, and greatest weaknesses.

They derive from the scientific method which was associated solely with the physical sciences and

was not designed or equipped to assess non-physical events. People may sense,

may believe, that their deeper beliefs and hope play an important role in

health, but modern scientific methods, which rely on clinical trials, cannot

possibly prove it.

Clinical trials require that a

set of rules be followed in order to demonstrate cause and effect, if present.[14]

The problem is that some of

these rules are not only impossible to follow when testing some non-physical

therapies, they actually prevent the practice of some crucial therapeutic

principles. They demand, if you like,

that the very factors which should be tested are removed – for instance a

highly individualised treatment plan, a focus on the therapeutic relationship

itself, a reliance on subjective measures of wellness, and so on.

If we are limited to scientific principles

in developing health care, then we will inevitably exclude a whole range of

healing experiences from trial. And of

course, if therapies are not proved to be successful, they won’t be funded.

Controlling

the range of treatment, by controlling what is acceptable evidence

is a way of controlling people. This is the politics of health. Worldwide, for example, there is a 7 billion

dollar market for anti-depressants[15].

Imagine what could be achieved if even the smallest fraction of this were spent on supporting people to heal

themselves.

The real

issues of spirituality and mental health do not lie in standardized categories

and definitions. They do not lie in the

area of information and proof, but in the area of wisdom and belief. And that,

in the garden of evidence-based medicine, is the biggest thorn of all.

Experience is the greatest

teacher of all and the teacher comes when we are ready to learn.

Here is my brain

in a pickling jar.

Note the tired synapses.

Observe the threadbare nerves.

Then tell me, if you will

where is my love of rain

my craving for colour

my vanishing dream?

12: HEALING IS CONNECTION, NOT CONTROL

Photograph. Rooftop Dragons,

Assisi, 1998.

Healing is about connection, not control.

A relationship based on power is control, not connection.

Healing is about connection, not

control. Relationships built on power

are not about connection, they are about control. Whenever one person says I am the healer and

strong and you are the patient and weak, then a healing relationship cannot

occur. If people treating others cannot

admit their own vulnerability then they cannot help them heal.

Why has so much of mental health

“care” actually involved taking away people’s freedom? I think it is because someone who is strong

enough to say they are weak is very threatening indeed.

On the other hand, when we are willing to

accept our own and other people’s vulnerabilities, we are human beings, being

human, at our very best. We are really

relating to each other. We are wanting

to connect rather than control.

How then, do people who set out

to heal others develop this ability? I

think there are two aspect to this. To

really see ourselves clearly and to make it possible for us to see the other

person clearly.

To see ourselves we need insight.

This is one of the most wonderful things we have, as human beings. It takes us beyond information and knowledge. Insight

is the key to wisdom. Information is

about facts. Knowledge comes from

integrating facts. But wisdom comes through understanding - standing under knowledge and letting the insight we gain from our own experiences

illuminate knowledge.

To see others, we need to be

able to negate ourselves for a while and look at the world through their eyes.

In a literary context, Keats called this “negative capability”. The ability to experience something outside

of oneself as if it were one’s self. I

think that this is how we open the doors of our perception and find the heart

of relationship.[17]

People who want to help others heal have to abandon the need for power and control utterly. Yet control lies at the heart of society.

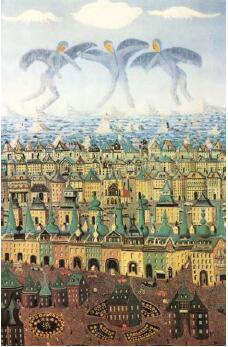

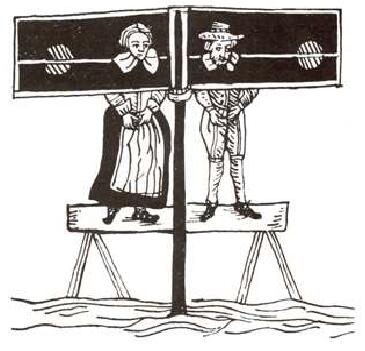

13: THE POLITICS OF DIFFERENCE

Woodcut. Pillory in Market Place. Anon. c 1600.

Societies

based on hierarchies of power control people.

Society is founded on the

politics of difference – the power struggle to be “better” than someone

else. People are classified and

controlled (by exclusion) on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, religion, age,

appearance, education, money, sexual orientation, and all manner of

abilities.

It is much harder, of course, to

classify and control a person’s inner world.

It is intangible, unseeable.

Maybe even inviolate, invincible?

It cannot be imprisoned – except perhaps by drugs. This means, to people

who need to control others, that a person’s inner world may be the most

threatening part of them. That is why is

it much easier to reclassify spiritual experiences as a sickness. And why it is

much easier to treat it in physical ways.

People fear what they don’t know

and don’t want to know what they fear.

Since what we fear must, by definition, be dangerous, people who

experience mental illness are called unpredictable, frightening, without

conscience, dangerous, demon-possessed.

So the uneasy dance between madness[18] and mysticism[19] continues, and the societal

need to contain people with mental illness is met. Society stigmatises, shames, silences,

sidelines, segregates, separates, scares and scapegoats them.

14: THE UNEASY DANCE OF MADNESS AND MYSTICISM

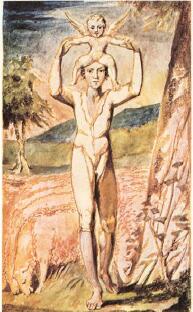

Engraving. Frontispiece, Songs of Experience.

William Blake, 1794

Defining

mysticism as madness is a way to control people.

A spiritual journey is the

sanest voyage we can make. Yet the major

hallmarks of spiritual journeys are so easily interpreted as symptoms of mental

illness.

As far back as we can see, it has been a

matter of political definition, (that is, the exercise of power by someone

else) whether seers and sages, mystics and magicians, poets and painters, witches and witch doctors,

shamans and saints, were deemed to have:

·

wisdom or illusions

·

visions or delusions

·

dreams or hallucinations

·

insight or insanity

How

easily we defile by re-definition!

“Oh, hello,

come on in. It’s Mr Blake. Mr William Blake, isn’t it? Well, come along in and have a seat. I’m Doctor Jones. Can I call you Bill?

Just a moment now while I look at this note from your GP.

Mnnnnn. So you’ve been

seeing angels again. And in a tree! Ahhhhhhhh.

Tell me, Bill, just to get things going here, exactly how many angels were in the tree?

Mnnnnnnnn

How many wings did they have?

Hmmmmmmn

And were they outstretched or covering their faces?

Who,

in their right mind would lead their people into the wilderness for forty

years, who would go off into a desert without food and water for forty days and

nights? Who would leave a family and

comfortable life in search of extreme austerity? Who would rule a vast country

yet live in utter poverty? Moving right

along from Moses, Jesus, Buddha, and Mohammed…

Yes, of course

I sometimes ask myself am I having a mystical experience or going nuts? Am I walking towards the light or into the

dark. But it is my question. Not someone

else’s. And it’s my answer.

Does that matter? Of course it does, because if someone else is

defining your personal experience, your status can change overnight from valid

to invalid (in-valid). That is very

dangerous, because then, the very ways

in which you heal might be interpreted as sick too. And no longer available to you.

·

A need to be solitary becomes unhealthy withdrawal. In fact seclusion has been given an entirely

new meaning.

·

A need for silence becomes hypersensitivity.

·

A need for rest becomes hypersomnia.

·

A meditative trance becomes losing touch with reality

·

Deep thought become disassociation

“Diagnosis is usually determined by someone

else, standing outside the person - someone else tells you what’s ‘wrong’ with

you. And diagnosis usually comes along

with a prognosis attached to it - someone else tells you what the outcome is

likely to be. But if all you have is

someone else’s diagnosis and prognosis, then your recovery might also be

prescribed by that. That is to say,

someone else will tell you when you are ‘right’. [20]

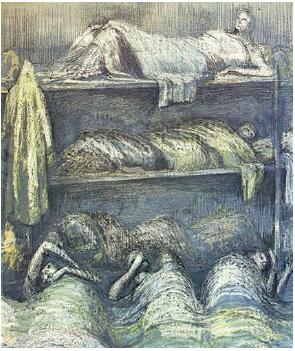

15: THE AGE OF BLAME

Painting. Shelter Scene, Sleepers.

Henry Moore, 1941.

Blaming people for their

mental illness is another way to control them.

The

next twist in the uneasy dance is when mental illness is seen as a divine

punishment or moral failing.

The word illness, comes from Old Norse (illr). It is interesting that for many years it was

mistakenly recorded as coming from the Old English yfel, evil and many texts were mistranslated accordingly.[21]

The fact that spiritual ease helps people deal with illness does

not necessarily imply that illness is a manifestation of spiritual

disease. That step of reverse

implication is a very dangerous trap.

Imagine being told you have a “soul sickness”.

One of the greatest fears I have about talking about spirituality

and mental health is that not only might we reactivate old bigotries, we might

create new ones, because we live in societies which foster blame and guilt.

“Oh, hello, come on in. It’s Mr Newton. Mr Isaac Newton, isn’t it? Well, come along in and have a seat. I’m Doctor Blake. Can I call you Zac?

Now let’s see what it says

here….Mnnn. So you’ve been seeing apples

falling again.

How many apples were there

exactly? Were they green apples or red?

And were they ripe when they fell?

Now are you sure you didn’t shake the

tree?

Come on now, Zac, think back. Are you sure you didn’t pull them off

deliberately?

In the Age of Blame it is easy to move from correlation to cause

to condemnation. Time and again, social

statistics become misinterpreted through social politics, and social fashion

starts to dictate health economics.

We are in danger of changing our health model from the ridiculous

biological determinism to the appalling economic determinism. Just look at recent messages in preventive

medicine. It is a short step from

saying:

1) Illness is inextricably linked to not being fit, being

stressed, exposing oneself to various kinds of poison.

to saying

2) Illness is a person’s own fault

to deciding that

3)

Support will be withheld.

What is so flawed about such arguments, apart from genetics of

course, is that it ignores the fact that many of us live in sick societies

which put a premium on perfection. I

believe that societies which expect people to be perfect, and so

create impossible goals, actually cause

sickness.

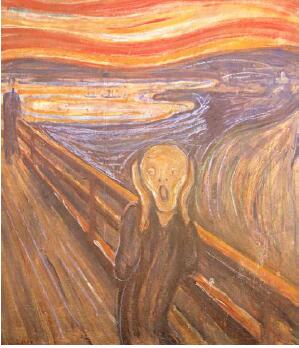

16: THE SPEED-NOISE SOCIETY

Painting. The Scream. Edvard Munck,

1893.

We live in an impossible

“got to be perfect” society.

We are the quick-fix society, the pill pop generation, who, in the

flick of a wrist can cheer up, grow hair, lose weight, stop smoking, have great

sex. Possibly, all at the same time.

We

live in a “got to be perfect” society, with mind and body police on every

corner. Health itself has become a market commodity, where health service

systems are run on absurd business models, so far removed from welfare that is

difficult for any one to fare well at all.

We are overloaded with information. We have hundreds of ways to communicate but

no time to talk to each other. We live

in a jargon world. A world of reversed

metaphors where the technical now explains the human. We used to say the computer is like a

brain. Now we say the brain is like a

computer.

Things which take time, people want NOW. Things they have now, they don’t want AT ALL. We are always being urged to be somewhere else and someone else.

Privacy is not tolerated. Boundaries are ridiculed. Silence is rare.

People rush around so

frenetically and noisily, maybe they are scared

to stand still. Scared of silence. Scared of space. Scared of their inner world – what they might

find there. Scared maybe, that it will

be full of empty echoes.

If we go fast enough, space

disappears. If we make enough noise, we

don’t need to listen.

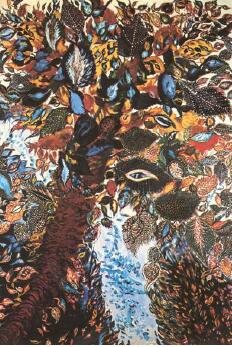

17: A TIME OF SPIRITUAL CHAOS

Painting. The Tree of

Paradise. Seraphine Louis, 1929.

We live in a time of chaos

where “spirituality” is sold in the market place.

There is agonising emptiness within our society which I think

reflects a desperate need for meaning, relevance, something deeper in

life.

Some people say there is a spiritual renaissance. Maybe there is a readiness for it, but I don’t think it has really begun yet. I think that we live in a time of spiritual

chaos. Old orders are in disarray. Familiar rituals are disappearing. New doctrines, new-age cults, supermarket

spirituality, all jostle for attention.

Many

of us seem to be scrambling for fashionable symbols and icons rather than deep

inner vision. We even have a global

religion, with an altar on every desk where we can connect with divine

intervention. All we have to do is press

the “save” button.

In

the mean-time, in the current climate of materialism, spirituality itself becomes another market

commodity. Or perhaps commercialism is a

new religion.

Many

of the old religions are making their pitch up-market. A church near me actually has a strategic

plan which it hands out on Sundays along with the hymn list. It even has a vision and mission statement,

which, I suppose, is appropriate.

I

discovered, while singing “Dear Lord and Father of Mankind”, the strategic

goals include:

·

worshippers must be restructured

around congregation committees called core groups

·

75% of worshippers must be

involved in groups.

And even more revolutionary:

·

prayer must be a priority

output.

Some churches seem to be

trying to jump the isolation gap by compliance bonding, where strangers are

forced to greet each other in freeze-frame intimacy. And at the church door, you can find a stand

with your name tag in a slot. You must wear your label to pray. Who’s here? Who’s not? Who’s late?

Who are you? Like my Grandad

clocking in at the mill - presumably if you lose your faith, you get given your

cards.

On bookshelves and on the web we are offered vast libraries to lead us into new-age self discovery, glittering with words full of food for the soul.

One internet site even offers a spirituality

assessment with a multiple choice questionnaire. Trying to make the mysterious, the mystical,

measureable. For the more scientifically

inclined, it explains “while the scoring is numeric and generated by an

algorithm, the interpretation is purely heuristic -- it takes place in your

mind and heart as you contemplate what your score might mean.”

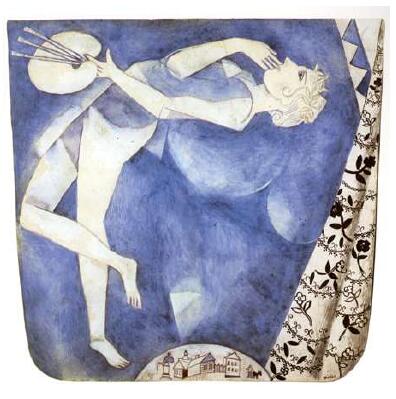

18: WORDLESS CONCEPTS

Painting. Painter: To the Moon. Marc Chagall, 1917

I still find intellectual

arguments about dualism frustrating. In

fact I can’t see the point of an intellectual

argument about wholeness. We might as well have a feeling session about intellect!

I know spirituality through touch, or a kind of sixth sense. When I am in that space I am whole. I do not experience myself in parts or even

dimensions or aspects or levels. I am

simply whole. To describe it in words,

in detail, means I inevitably present self as something fragmented.

As Mental Health Commissioner, I came across the word spirituality all the time. But hardly anyone ever said what they really

meant by it. Sometimes I felt people

were just trying to be “spiritually correct”.

“Oh, yes. Remember the spiritual dimension” they’d

say, eagerly ticking off their quality control matrix, hoping to get high

ratings on the performance indicators.

We pay lip service to things we can’t or don’t want to talk

about. And, anyway, these days people

only want to talk about what they can measure.

We don’t seem to have the words to talk about spirituality any

more. Maybe we have lost the words. Maybe it is because the concept has become

so remote. Or maybe it is embarrassing

for us talk about something so ephemeral in our materialistic world.

Maybe the words we did

have are archaic or ambiguous. So we

hold our tongues. And the distance

between people gets greater, and possibility of relating, more remote. Or perhaps we are really dealing with

something that is a wordless

concept. Something beyond words. We just don’t

have words to describe our wholeness, our oneness, our spiritual self.

Imagine

walking backwards, away from words. Let

go of your verbal skills. Let go of your

word pictures. Walk away from them. Lose everything but awareness of your

self. Then stand still, be silent. Do

you experience yourself as whole?

Before Words[22]

In his cave, he had no nouns

this man-pre-man. Imagine

the absence of thought.

It makes no sense.

So sense was all.

Picture following the voice

of gods and demons

in everything.

But then there were

no names.

No givens, to distinguish

right from wrong

from reason.

Only two rooms

and locked out of one.

Without words, what

becomes of connection?

With them, what

does connection

become?

19: MAKING SPACE

Photograph: Birds in Sky,

1998.

To look within ourselves, we

need to make space. To

share what we find, we need to take a risk.

One of the greatest difficulties

for me in writing this talk was that I was constantly trying to find words for

wordless concepts. And probably one of

the greatest difficulties for you listening to me has been trying to find the

wordless concepts amongst my words!

So let me now summarise the main

points I tried to make:

Firstly, I ask you to think

deeply about something I said right at the beginning: We are all weak. We are all

strong. We are all wounded. We are all healers.

I believe we are at this

conference because we want to heal the mental health system. That means we need

to recognize our innate abilities and through that connect - with ourselves and each other - because healing is about connection.

It is very difficult, in a world

which values being perfect and invulnerable,

to acknowledge vulnerability, but we must transcend those difficulties. When we can connect

with our own experiences of

vulnerability and accept other people’s vulnerability without judgement, then

we can connect with each other, rather than control each other.

As

members of The World Assembly on Mental Health, we have certain

responsibilities. One of them is to

question the politics of health. It

is our job to challenge any medical control of mental illness which limits

people to physical treatments. We must also challenge the economics of blame

which actually withholds treatment.

It

is also our job to confront social control of difference and expose ridiculous

notions of perfection. We must declare

and demonstrate that experiencing mental illness, in whatever form, is not

something to be ashamed of. Indeed, that

dealing with mental illness is something to be proud of, because it gives

people a gift of insight. It can give

people greater strength of character, capacity for

compassion, a stronger sense of self.

We

should also be clear that being imperfect is one of the hallmarks of being

human and lead the way by saying that illness teaches

us about being well, vulnerability teaches us about being strong, loss teaches

us about finding.

When

we let go of our prejudices and mind-sets, we begin to understand the worlds of

other people. Negate ourselves for a while, as Keats would have said, in order

to see the universe through other people’s eyes. Then, even if we do not

recognize our own spirituality, we

may see that, for others, spirituality is intimately linked to health. That spirituality is a deeply personal

experience which can be crucial to understanding and healing mental

illness.

When

we are dealing with the mysteries of life, we need to put aside the search for facts. Then, we will discover that insight is the

teacher. This takes patience. It takes time and space. It means tolerating ambiguity, and instead of

going out to get knowledge, waiting for wisdom to find us.

Let’s

try to speak and listen to each other in different ways. See as if we were

blind. Speak as if we were mute. Listen as if we were deaf. Trust our instinct more.

If

we are willing to make more space to listen, and let time do its job, then, I

believe, that just like the man upstairs, we will hear.

So let’s make space for ourselves and each other throughout this conference. If we make connection our goal, rather than control, we may see miracles!

20: RETURNING TO SIGNS

Photograph.

Vancouver. World Congress

Website, 2001.

Make space, let time do its

job, and see what happens next.

Some

months ago, before I was invited to Vancouver, I came across a name I hadn’t

met before, and I came across it in a very strange way.

I

happened to hear about a childhood friend of mine whom I hadn’t heard of in

forty years. It came to my attention

that this friend had translated some work by a French, Jewish,

neuropsychiatrist called Henri Baruk[23].

I

was curious and followed this up. The

work was to do with spirituality and mental health. I was even more curious and went to some

lengths to get a copy of one of his books.

Henri

Baruk was a revolutionary, who argued that psychiatry was a “moral discipline”,

deeply related to spirituality. He

lamented that “the evolution of

psychiatry has caused the moral aspect to be neglected in favour of purely

technical solutions”, which, he said “I

consider to be a great error”. He

told his own story, how as a psychiatrist,

with such ideas, he continually had to fight to be heard. I found his

story, like all stories, precious. I

only wished I could have met Baruk, but he died two years ago.

Several

weeks after this discovery, I was asked to give the Mary Hemingway Rees

Memorial lecture in Vancouver. I tried

to find something out about Mary Hemingway, and who else had given this

lecture. I came across only one

name. The person who gave the Second Rees Memorial

Lecture. It was at Edinburgh

University. Forty years ago. His name was Henri Baruk.

I imagine that my message today has been similar, in spirit, shall

we say, to his. Maybe that’s not such

good news. Has nothing changed in forty

years? Well yes, of course it has.

There have been many improvements in mental health care in recent

years, in many parts of the world. One

of the most crucial developments has been the survivor movement which has

broken through walls of silence and insisted that people who experience mental

illness have something to say, which is worth listening to.

I doubt that at that World Congress, forty years ago, there would

have been so many survivors, or so many people prepared to talk about their own

vulnerability. And this year, I believe

for the first time, a survivor has given this lecture.

The

past year has been one of tidal changes in my own life. Changes in state and status at every

level. Solitude and silence have been

paramount. Trying to fathom the depths

of my spirituality has been the one thing which has kept me anchored when I was

totally at sea. In fact, it ensured my

mental health. And I learnt once again, that we never know whether we are at

the end of one journey or at the beginning of another.

By the time I had written this talk, I knew that was the reason I

was called to give it. So I would be able to come to Vancouver and tell you

that.

Maybe you came because you needed to hear it?

Thank you

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people helped me with this talk by sharing ideas, commenting

on drafts, or just saying something I needed to hear. I particularly want to thank Dr Robert

Miller, Doug Harvie, Betty Munnoch, June Read, Ann Goodwin, Tessa Thompson,

Margaret Thompson, Dr Patte Randal, Dr Vernon Jantzi, Dorothy Jantzi, Bernard

Jervis, Ruth Manchester, Dr Syd Moore, Rae Nicholson, Roger Hewitson, Kim

Saffron, David Guerin, Linley Rodda, Dorothy Kay, Mary O’Hagan, and Dr Steven

Thompson. And special thanks to Barry

Lent, for leading me to Henri Baruk, to Robert Miller for sharing his

delightful jokes, to Tessa Thompson and Sven Mehzoud for helping me prepare the

overheads, and to June Read for an infinite supply of hot soup during a long

cold New Zealand winter.